- Home

- James Lovelock

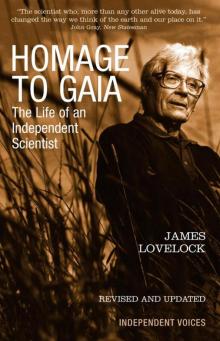

Homage to Gaia

Homage to Gaia Read online

Homage to Gaia

The Life of an Independent Scientist

James Lovelock

Souvenir Press

I dedicate this book to my beloved wife Sandy

Foreword

When this book was first published in 2000, I was already 80 years old and did not expect that the next two decades would bring much that was memorable and worth writing about. As it has turned out, I was completely wrong and the last 14 years have been as active and full of excitement and pain as my earlier life.

In 1999, Sandy and I decided to commence the new millennium by walking England’s longest footpath, the one that goes from the small seaside resort of Minehead down the north coasts of Somerset, Devon and Cornwall to Land’s End and then proceeds eastwards along the South coasts of Cornwall, Devon and Dorset to the ferry terminal at Sandbanks. The walk is formidable, even for the middle-aged, being 630 miles long and with 110,000 feet of cliffs to climb.

We did it in a series of one to three week spells, most of them during 1999. The total walk took 14 weeks and we treasure it as one of the most pleasurable and fulfilling achievements of our lives. At the time we walked, England had one of the world’s most beautiful and exciting coastlines. Indeed part of it, the Jurassic Coast that goes around the southern coast of Dorset, has been chosen as a World Heritage site. I use the past tense about this scene of unparalleled coastal beauty because we did our walk before politicians with a liberal tendency began their act of demolition. They are replacing what was once splendour with monstrously large wind turbines and they say they do it to ‘save the planet’. Their puritan forebears vandalised another kind of beauty ‘to save our souls’.

I am deeply moved by our countryside and the coastal scene but I am a scientist and know that if we want to live well with the Earth we need, first of all, to understand it. Even the best of our environmental scientists know as little about the Earth now as did the best physicians on the battlefield at Waterloo know about the bodies of their injured soldiers. We try to do our best but science is slow to find a cure. It helps to keep in mind that arrogant certainty is the antithesis of science.

Do not for one moment believe that installing wind energy on the Devon coast will “save the planet”; instead, it will hugely profit large landowners, the German economy and those whose livelihood is sustained by the subsidies we pay that have been craftily hidden in the cost of fuel.

Those who know me will sense desperation and indeed I am desperate, for already the North Devon coast begins to fill with regiments of these grotesque forms of renewable energy. How long I wonder before the scene of beach, sea and sky is transformed into an industrial landscape of power plants?

What I have just written is a small part of the topic, climate change. It has kept me unusually busy during these past years. It all started in 2004 when I first became aware of the possibilities of serious adverse climate change if nothing was done to stem the yearly increase of greenhouse gases. I was not alone. The distinguished author, Tim Flannery and the American vice presidential candidate, Al Gore, were both writing books expressing their warnings and solutions while I continued writing my book and called it The Revenge of Gaia. It didn’t mince its words; indeed, one journalist referred to it as the scariest book he had ever read.

By 2007, when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) made projections of the rise of sea level that disagreed with observations by competent scientists, some of us began to wonder how valid projections of the climate deduced from mathematical models were. The climate scientists and mathematicians who constructed the models were among the best in the world and we trusted their competence. The trouble was that neither we nor they knew enough about the Earth itself, and we were especially ignorant about the climate of the ocean.

The weather and the climate we know personally come from contact with that insubstantial gas that is the air; but its ability to store the heat arriving from the Sun is 3000 times less than the storage capacity of the ocean.

Water is by far the most important substance on the Earth. Without it there would be no life of an organic kind, and a climate like that of Venus but not so hot. We cannot ignore the climate of the ocean when we try to calculate the temperature of the Earth. The ocean stores heat in subtle ways and its lower layers are as cold as 4°C. We should keep in mind the wise words of the climate scientist, Ken Trenberth, who recently said “we do not know where the heat from the Sun is going”.

To those of you who would like to read more about my views on this increasingly complex topic there is my book “The Vanishing Face of Gaia” (2009) and another due to be published in the spring of 2014 by Allen Lane/Penguin.

Despite the fast changing world Sandy and I have delighted in the last 14 years. Remarkably our romance that began in 1988 has remained as strong as ever as has our love for one another. I doubt that I could now walk the 630 miles I did in 2000, but I am fairly sure that Sandy could; even so we are still healthy and enjoy walking the six or more miles of coast path that now goes past our home.

I was proud and deeply moved in 2003 to receive from Queen Elizabeth II the invitation to be one of her Companions of Honour (CH). The singularly beautiful medal that goes with the honour she presented to me at Buckingham Palace in 2003 at the start of a 10 minute private audience.

Gaia and the thoughts and consequences of that seminal word will be with me so long as I live, and so will my gratitude to Bill Golding for his gift. But from the beginning many of my colleagues viewed it with disdain. It has been called by distinguished scientists, ‘not science, but an evil religion’; others have referred to it as merely ‘fairy stories about Greek goddesses’. Rarely, perhaps never before, has the name of a scientific hypothesis stirred so much anger and contumely.

As time passed Gaia’s fortunes rose and fell but in 2006 my cup was filled when the Geological Society of London awarded me their highest honour, the Wollaston Medal. At last after nearly 40 years of rejection Gaia was recognised in one of the footholds of respectable Earth science.

As time passed after the millennium we both found living at Coombe Mill increasingly difficult. For me it was a matter of taking care of 40 acres of meadow and woodlands mostly by myself as well as doing independent science and writing books. In addition, the consequences of our government’s faith in renewable energy so increased the cost of energy that by 2007 it was costing us £6000 per year merely to keep warm in our Devon house. We used our savings to buy a house in Midwest America where the yearly cost of heating, even when winter temperatures fell as low as -20°C, was only £600.

In 2010 we decided to move from Coombe Mill to a small coastguard cottage on the Chesil Beach in Dorset. We are now downsized to four and a half rooms in a tiny house only 70 yards from the edge of the sea and on part of our beloved coast path. We are now as happy as it is possible to be.

Max Planck, the originator of quantum theory said “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it”.

The truly distinguished biologists, William Hamilton and John Maynard Smith, strongly rejected the Gaia hypothesis but both of them changed their minds before they died, and I have their personal letters welcoming the hypothesis back to proper science and these letters are held by the Science Museum of London in their archive of my papers.

Although their places in the geography of science are far apart, quantum theory and Gaia share much in common. I will finish this introduction with another quote from Max Planck that reveals how much we shared a similar attitude to science and our way of doing it. He said in 1936 “New scientific ideas never spring from a communal body, however orga

nised, but rather from the head of an individually inspired researcher who struggles with his problems in lonely thought and unites all his thought on one single point which is his whole world for the moment”.

24.11.13

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword

Preface and Acknowledgements

List of Plates and Figure

List of Abbreviations

Introduction

1. Childhood

2. The Long Apprenticeship

3. Twenty Years of Medical Research

The Voyage on HMS Vengeance in 1949

4. The Mill Hill Institute

The Year in Boston

My Last Years at the Mill Hill Institute

5. The First Steps to Independence at Houston, Texas

6. The Independent Practice of Science

Shell

The Security Services

Hewlett Packard

Inventions

7. The ECD

8. The Ozone War

The Voyage of the Shackleton in 1971–2

The Voyage of the Meteor in 1973

9. The Quest for Gaia

10. The Practical Side of Independent Science

Computers

The Royal Society

The Marine Biological Association

Living in Ireland

Coombe Mill

11. Building Your Own Bypass

12. Three Score Years and Ten and then the Fun Begins

13. Epilogue

Index

Plates

Copyright

Preface and Acknowledgements

The story of Gaia is an unfolding drama, and my acknowledgements to those who participated in it are like a cast of characters at the beginning of a play. There were many actors in this thirty-five-year show, heroes and villains, and I have listed them in the order of their appearance. I thank them for their proper criticism, support, and encouragement during the many rehearsals of the Gaia story as it went from a mere notion about detecting life on other planets to its debut as a theory in science.

Carl Sagan, Dian Hitchcock, and Louis Kaplan—all then at JPL (the Jet Propulsion Laboratory)—were the first to listen and seem interested in my idea that somehow life at the Earth’s surface regulated the chemistry of the atmosphere. I am so grateful that they did not pour scorn on my ideas. Peter Fellgett was the first scientist in the UK to hear me, and he responded with agreement tempered by thoughtful criticism. Over the years, he and his family became close friends, and he has been a staunch supporter throughout the long period when Gaia was unpopular with scientists. Norman Horowitz, Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technology, disagreed with me over Gaia but was a friend and his criticism was fair. I owe a special debt to my neighbour in Bowerchalke, the novelist William Golding. What luck to have my theory named in 1967 by so competent a wordsmith and Nobel Laureate.

Most of all I acknowledge my friend Lynn Margulis, who joined me in the development of Gaia in 1971. She put biological flesh on the bare bones of my physical chemistry. She has courageously supported Gaia in spite of hostility from parts of the United States scientific community—that sometimes threatened her own standing as a biologist.

From 1967 onwards, James Lodge has given me wholehearted support and encouragement. I acknowledge especially the introduction he gave me to the scientists of NCAR (National Centre for Atmospheric Research) and the opportunity to discuss with them Gaian aspects of the atmosphere. This was crucial in the learning phases.

The worst thing that can happen to a new theory is for it to be ignored. I therefore acknowledge the robust, even scathing, criticisms from Ford Doolittle, the microbiologist from Halifax, Nova Scotia, and from Richard Dawkins of Oxford. They hurt at the time—1979 to 1982—but they made me think and tighten what had been a loose hypothesis into a firm theory. Much friendlier was the constructive but firm criticism from the eminent geochemist Professor HD Holland of Harvard University. We have sustained a warm respect for each other and he was an outstanding presence at our meetings in Oxford. In no way do I cast these critics as villains; they are open in their dislike of Gaia.

Professors Christian Jünge and Bert Bolin were influential in Gaia’s development by inviting me to present the first paper on Gaia at an open scientific meeting in Mainz, Germany. Bert Bolin, through his connections with the Swedish journal, Tellus, invited me to submit the first joint paper with Lynn Margulis for publication. It appeared in Tellus in 1973 and I acknowledge the splendid open-mindedness of that journal, which continued to publish Gaia papers throughout the time it was unacceptable in most mainstream science journals.

Professor Peter Liss, of the University of East Anglia, was the first to recognize the significance of my measurements of dimethyl sulphide (DMS) and other gases in the Atlantic Ocean: his paper on the flux of DMS was one of the key papers in Gaian research. Professor Andrew Watson, now of the University of East Anglia, joined me as a Ph.D. student in 1976 and did the first experiments that showed the relationship between atmospheric oxygen abundance and the probability of fire. This was an essential step in the understanding of the regulation of atmospheric oxygen. Andrew has become a friend and a critical supporter of Gaia.

Professor Robert Garrels of St Petersburg University in Florida was the first of the geological community to give wholehearted support to Gaian ideas, and continued to do so until, sadly, he died in 1988. He and his wife Cynthia were warm friends. Lord Rothschild was one of the few biologists to accept Gaia in the early days of the 1960s and 1970s, and he gave from his position as co-ordinator at Shell Research Limited, tangible support. Sidney Epton, also of Shell Research, wrote with me a landmark paper in 1975 in New Scientist, entitled ‘The Quest for Gaia’. It was this paper that stirred publishers to invite the writing of my first book.

Another scientist who gave moral as well as practical support was Lester Machta, Head of the Air Resources Laboratory of NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), and to him and his wife Phyllis I shall always be grateful. Tony Broderick, who became the Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration, FAA, was another senior figure who warmed to my ideas about the Earth during the 1970s and 1980s.

From its introduction in 1968, a small group of scientists, distributed around the world, found time, but not money, to develop Gaia theory. Among them were Greg Hinkle, one of Lynn Margulis’s students, Andrew Watson, Peter Liss, and Mike Whitfield. Although not about the Earth as a system, Eugene Odum’s writing and research on ecosystems took the same top-down view and suffered the same misunderstanding by conventionally minded biologists. I salute him as our closest predecessor.

Professors Robert Charlson and Ann Henderson-Sellers argued that Gaia was a valid topic of science, against the strong tide of contrary opinion. Bob Charlson was the lead figure of the famous Nature article of 1987, linking algae, dimethyl sulphide, clouds, and climate. He, Andi Andreae, and Stephen Warren did much to make Gaia respectable, and Bob has remained a staunch supporter ever since. Professor Chris Rapley, during his presidency of the International Geosphere Biosphere Programme, and directorship of the British Antarctic Survey, has done much to make Gaia visible. The climatologists Peter Cox and Richard Betts, of the Hadley Centre, have lent their support, as have Professor Brian Hoskins and Paul Valdes and Bruce Sellwood, all of Reading University. The Open University was wonderfully supportive when Gaia was unpopular in science. I am especially grateful to Professor Robert Spicer for his paleobotany that did much to make environments of the geological past come alive. Professors Dee Edwards and David Williams and Peter Francis of the Open University gave unstinted support.

In the USA the seeds of Gaia found a harsher climate. For many years, Lynn Margulis, Bob Garrels, and Robert Charlson were alone in writing and working on Gaia. It was not until 1989 that David Schwartzman and Tyler Volk wrote their important paper on rock weathering and confirmed it as a Gai

an mechanism. Lee Kump and Lee Klinger, in the last ten years or so, have established a presence in Gaian research, but it has not been easy for them against the disapproval of their scientific community. The same was true for Tyler Volk as is shown by the guarded Gaian support in his book Gaia’s Body. I acknowledge their staunch support and welcome the book The Earth System by Lee Kump, James Kasting, and Robert Crane. Connie Barlow’s books From Gaia to the Selfish Gene and Green Space, Green Time provide, through different eyes from mine, a historical account of Gaia’s evolution. Larry Joseph’s warm-hearted book Gaia: The Growth of an Idea tells the history of Gaia and the personalities of the actors.

The first scientists to establish a fully funded programme of Gaia research were John Schellnhuber and his colleagues at the Potsdam Institute in Germany. They have constructed the most detailed and impressive models of a Gaian world and confirmed its inherent robustness. Their book, Earth System Analysis, is the first professional application of Gaia theory.

Stephen Schneider and Penelope Boston, although critical, felt that Gaia should be treated as a scientific topic, and organized the meeting at San Diego in March 1988. Professor Peter Westbroek, of the University of Leiden, hosted the meeting on the Island of Walcheren where the first Daisyworld paper was presented. Peter has kept the idea alive on continental Europe ever since. In Catalonia Professor Ricardo Guerrero has worked and written on Gaian topics and is a friend.

Japan has done much to encourage the development of Gaia. Walter Shearer of the United Nations University (UNU) in Tokyo first invited me there in 1982. That unusual university supported work and meetings on Gaia in the bad years of the 1980s, and we tried, sadly without success, to build a generation of affordable scientific instruments for the developing world. Through Fred Myers of the UNU, we first met Hideo Itokawa and his wife Ann in September 1992, and so established a bond of friendship with Japan. Hideo was a staunch supporter and translated my third Gaia book The Practical Science of Planetary Medicine into Japanese. The Japanese scientist Shigeru Moriyama introduced Gaian science to Japan, and is a familiar figure at our Oxford meetings. Since April 1993 Yumi Akimoto, President of Mitsubishi Materials Corporation, has continued to support the idea of Gaia. He and his wife Sadako have become our friends. A more complete account of our experiences in Japan is given in Chapter 12.

Homage to Gaia

Homage to Gaia